By Anna Potapova and Arnaud Frattini

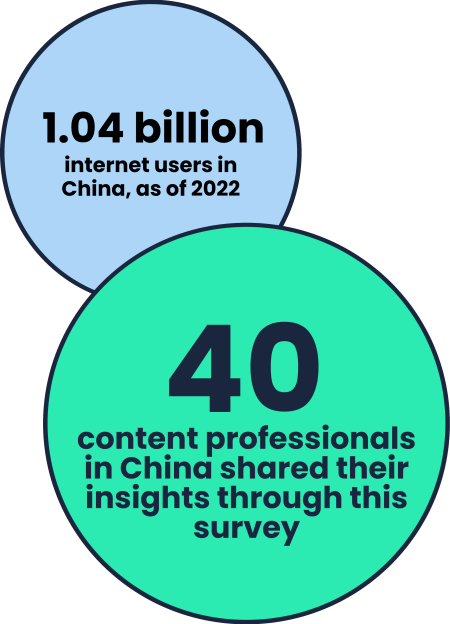

With over 1.04 billion internet users as of 2022, China has become a breeding ground for innovative applications like the e-commerce giants Taobao, Pingduoduo and Jingdong. These platforms offer millions of items at prices that seem almost unbelievable.

While online payments like Alipay and Weixin Wallet ensure secure and effortless transactions, logistics companies like Cainiao and Shunfeng deliver your purchases in less than an hour, making them an integral part of daily life for hundreds of millions.

However, what’s unique is that these experiences are created without dedicated content designers and UX writers*. If content design is as crucial to user experience as we believe, how is it possible to build this “digital paradise” without it? Why is it that some Chinese companies have started hiring content designers, and some have yet to hire any?

To answer these questions, we interviewed over a dozen UX professionals across China. Forty content professionals based in Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hangzhou shared their insights through these surveys.

In our research, we will explore the specific characteristics of China’s tech landscape and how it impacts UX design and content, define the factors that make Chinese companies change their mind about content designers, outline the challenges faced by content professionals, and formulate some trends that are shaping the future of content design in China.

*Here and below we will use these terms interchangeably, to refer to professionals who create and optimize the content that users interact with in digital products and services.

Emerging from relative isolation just a few decades ago, China has redefined innovation through a unique blend of entrepreneurial spirit and fierce competition. Unlike the West, China’s engine wasn’t fueled by centuries of wealth, but by government support, lower labor costs, and a massive population yearning for opportunity.

Affordable mobile phones and mobile traffic made it possible to cater apps and services to a wider audience. However, these factors contributed to a highly competitive business environment, where outrunning the competition is crucial, and overtime is often a norm.

Access to a large user base and relatively low development costs allows some companies to run bold experiments. Instead of going through a week-long sprint to define user needs and evaluate potential solutions, a tight team composed of a product manager, an engineer and a UX designer can design and launch a new feature in as little as under 2 weeks. This approach leaves little time for user testing, or to think about the logic and consistency of the microcopy.

When competing over the demands of Chinese consumers, core business propositions that set them apart from the competition must be created. While UX content can make or break the user experience in games or wellness-related apps, the core value of the most used Chinese apps is defined by the services it can deliver, as explained by Chao Guo, a senior UX Designer at AliExpress:

“When your business is just taking off, it might be less important how polished your copy and UI are, as long as you provide unique service with a good value. People here [in China] tend to focus on service.”

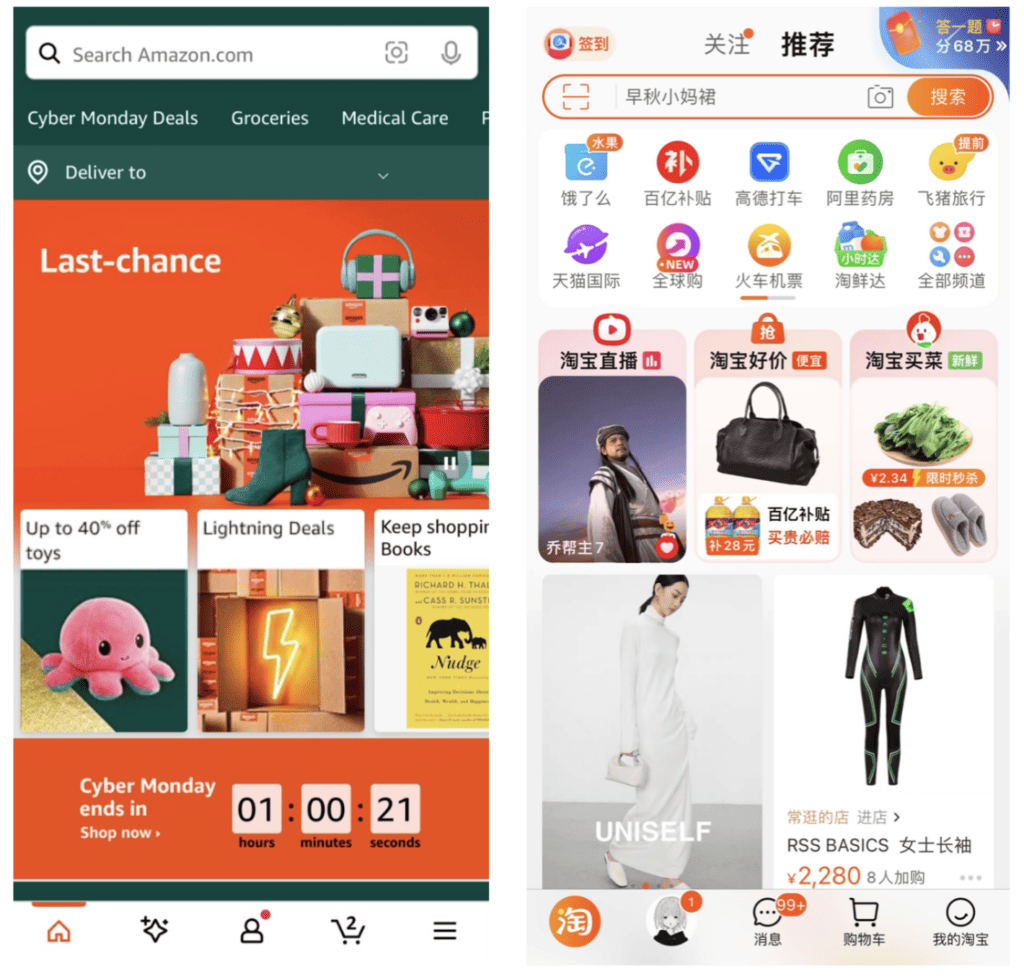

Mobile users in China tend to have little issues navigating complex interfaces and dense information layouts. Take a look at Amazon (left, designed in US) and Taobao (right, designed in China) homepages. There are 32 words in total on the Amazon screen (excluding personal details), and 63 words on the Taobao screen, making it almost 2 times denser!

The dense layout is standard practice in Chinese apps, as pointed out by Yuan Qing Lim, a Staff Product Designer at Shopify. In his talk on UX in China, he says that when facing an interface built on the “less is more” principle, Chinese users are not satisfied by the lack of “real” content: while it doesn’t have any useless information, it also has less useful information. Yang Zhong, a Lead UX Designer at Ergosign GmbH, shares a similar observation: “For many people in China, more correlates with value.”

In addition to a preference for dense layout and abundance of information, Chinese users tend to have an easier time with less explicit copy.

According to Erin Meyer’s “Culture map”, China is defined as a high-context culture, meaning that communication relies on shared knowledge and implicit cues. US and some European countries lean towards low-context communication; in those places, people prefer direct communication, making explanation crucial for app design.

For online banking, an American app is more likely to provide step-by-step screenshots with instructions for transferring funds, ensuring clarity for less tech-savvy users.

In contrast, the same type of app in China provides less background information for the same task, and directs users to customer service for details.

It can be argued that the very nature of low-context communication was a significant factor in making the practice of content design so successful in Europe and North America.

Content designers are needed to make brand-generated content accessible to a wider audience with different backgrounds. In China, when your audience can quite literally read between the lines, the importance of content design naturally declines.

During our research, we couldn’t find a single Chinese company, serving a local market, that hired a dedicated content designer to work on their microcopy. However, we did find a few Europe-based companies, expanding into the Chinese market, that hired content designers to work on their apps.

Of course, there are exceptions: some companies hire content designers to work on chatbots; we can also see UX designers in companies like Taobao and Tencent advocating for clarity and educating their stakeholders about the value of clear UX writing (sources in Chinese: 1, 2). This changes, though, when Chinese companies decide to expand and cater to the international audience.

To match the speed of business, everybody writes. This includes product managers, developers, and designers. In dealing with this situation, a UX designer working on a food delivery app (who preferred to stay anonymous), shares these insights:

“Not only is content considered a team effort, but we also believe that copywriting is a basic skill, that is to say, everyone should master it. We don’t have a specialized dedicated team looking at the content as a whole. Most of the writing decisions are made at the moment, and resolved on a requirement level rather than platform level.”

This also lines up with what Betty Xi, former Design Lead at Airbnb in China, is describing:

“People in China think that they have a stand with the language. Everybody understands this language, they can write a line or two, they can write a paragraph or two. So in China, people think that everybody is a writer, but in the English-speaking world people think that professional writers are needed to do this kind of work.”

Content designers in China find themselves in a recurring situation. To the companies, writing is not dedicated to a specific team, and “anyone” could develop writing as a basic skill.

In this situation, content designers normally face two main challenges:

– First, they need to explain and promote the value of their discipline to stakeholders, changing perceptions about writing.

– Second, they often have to compete for control of writing tasks with other team players like sales, marketers, designers, and developers, ensuring they have a significant role in the process.

In companies with established content design teams, team members face challenges similar to other markets, such as being spread too thin across multiple projects. They have to strategically choose their battles, opting for lighter involvement in lower-priority projects while focusing more on critical, core projects for a more impactful content-driven design approach.

In the Chinese market, there’s a distinctive emphasis on engineering over design and content when rolling out new features or products, driven by “ship first, decide later.” As Betty Xi points out:

“As a Chinese person, I would say our culture is more focused on efficiency and broader things rather than smaller details. Leadership here tends to pay more attention to engineering and project management because they think that the function of an app is way more important than the details, like the look and feel of a page. So they always wanted to prioritize their efforts into the bigger, broader thing. Do the big thing, and do it effectively. Move faster than your competitors.”

In China’s highly competitive tech industry, the fast pace of competition often clashes with the attempts of Content designers to do things right for international audiences. Content designers must constantly re-adapt, conducting user research on the fly, and competing for influence in conversations dominated by product managers, developers, and designers.

In China, evangelizing stakeholders for improved collaboration processes extends all the way to the leadership level. According to our survey responses, a common challenge is the “lack of recognition for content strategy” among leadership and the organization.

“[it’s hard to] get buy-in from key decision-makers about the high-level issues that need to be solved across business units and departments. We provide insightful suggestions and strong evidence to back up why things should change to make our overall communications clearer and more effective, but they are rarely taken seriously, or the resources aren’t available to implement these strategies.”

As Content design is still in its formative stages globally, many of the challenges faced in China can be similar to those found abroad. However, a significant difference in these issues comes from Chinese business leaders. As they do not always fully comprehend UX or feel the need to prioritize it in the product development life cycle, they pose an additional challenge for content designers.

For these designers, bridging the gap between the comprehension of UX and the need for products suitable to international audiences becomes a complex task. They must take the time to educate them on international UX practices: advocating for differences such as low-density information and the importance of a consistent brand voice.

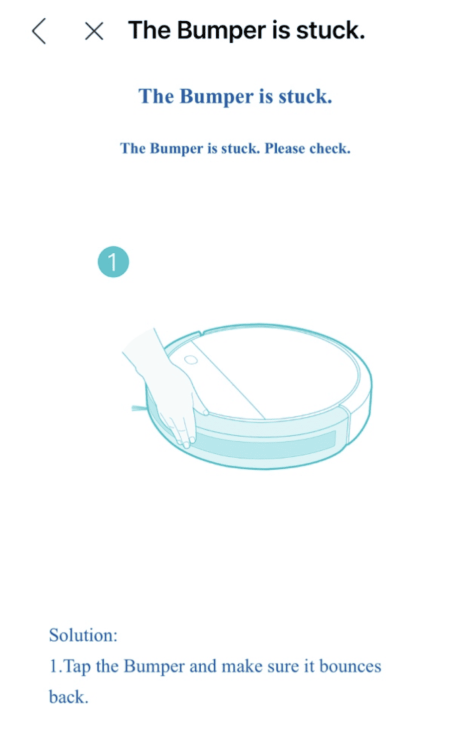

This vacuum robot application, presumably translated directly from Chinese, exhibits repetitive and unclear information, suggesting a potential lack of input from a Content Designer in its development process.

While expanding globally, Chinese companies eventually recognize the need to readjust their UX practices with the language and culture of their target audience.

Initially, efforts involved transitioning from machine translation to hiring language experts proficient in target languages. These experts not only handle localization, but often find themselves writing interface content, contributing significantly to the overall user experience.

Many content designers often start their journey as translators or localization specialists before gradually transitioning into content design and UX writing. This journey parallels an observation made by Larry Swanson regarding the initial translation background of content designers in Europe.

In our survey, one-third of respondents identified themselves as “localization specialists,” underscoring the common trajectory of professionals in this field. Freelance content marketing and UX writer Sabrina Valles shares this observation:

“When it comes to marketing and content-related roles, there’s often a misconception. Companies might hire foreigners, but mainly for translation, not recognizing the difference between translation and content strategy […] Many Chinese companies hire foreigners for translation without considering the strategic aspect of content.”

These content designers face a unique challenge — the misinterpretation of “content” (内容) for “language” (语言), which leads to the prevalent misunderstanding that having content written in the target audience’s language is sufficient enough. As one of our survey respondents pointed out, “even if [copy] was fully translated into the other language, it’s still hard to understand for some native speakers”.

These professionals often find themselves in the role of explaining the nuanced differences between language and content. They must show that creating usable, useful, and clear content, intertwined with interface design, is essential for a seamless user experience. Despite these efforts, organizations tend to revert to old habits and misunderstand language as the primary focus, overlooking the comprehensive role of content.

Finally, in this emerging discipline, the community of Chinese content designers is small. Unlike in other markets, this community does not seem to have strong ties to each other.

There are no regular meet-ups, offline or online events, or one-day conferences with organized workshops. There is no private training or workshops, design schools are not teaching UX writing. At the time of this writing, the only book available in Chinese on the topic is the translated version of “Writing is Designing” by Michael J. Metts and Andy Welfle.

When transitioning from localization experts or content marketing/journalism to content design, content designers are often self-taught, relying on resources found online or in books, often coming from abroad. While some designers are publishing their UX writing tips and starting the conversation online, a community between practitioners has yet to solidify, as mentioned by the UX designer from the food delivery app:

“I’m not sure how things are overall in China, but I can tell that there are some designers posting about their content studies on some WeChat accounts. So maybe there are more designers working on that than I know.“

This last challenge should not be underestimated. In other markets, the success of content design and its gradual adoption among companies is due to the strong support that content designers have for each other and their ability to organize themselves as a community.

Between Chinese companies operating locally and globally, there are significant differences in the speed of adoption of UX and content design.

Such organizations are in the early stages of adopting key UX practices, like conducting user research, including user feedback into the product development process, prototyping, and testing with users before launching. However, there’s limited indication that interest in content design will increase, according to multiple interviewees:

“I don’t think there will be too much change in the near future […] it looks like the situation is not going to change too much, unless it will be some new business experiment, like overseas operations that require more content research.” – UX designer from the food delivery App

Chinese organizations may have to rethink their understanding and degree of adoption of content design as local competition escalates, as Andy Carney, former Head of UX Writing for Trip.com would seem to say:

“In China, a few products control the market, like Taobao. If you don’t use Taobao, what do you use? There’s no real benefit for companies to improve their products as long as users continue to accept it.”

One potential new trend that could disrupt the status quo is the growth of the ‘silver economy.’ The Chinese population is aging rapidly, leading to an increase in the number of elderly people using digital products. This demographic shift may require companies to reconsider how they approach UX design to better cater to the needs of older users.

For those Chinese companies operating globally, despite the challenges, there is a noticeable effort to project a global image, as explained by Sabrina Valles:

“Many Chinese companies want to project a more global image, especially sounding like a US company. They often hire individuals like me to add that American touch to their content. Even in live streaming, they prioritize the US accent and branding.[…]

The growing recognition of content design’s importance in China may lead to the bridging of local practices and global content design standards. With more of these companies looking to expand globally, influenced by international success stories like SHEIN and TikTok, they may find that prices, quality, and speed of delivery are not the only sufficient competitive advantages.

There may be a realization that adopting international UX practices is crucial for success. As awareness and recognition of content design gradually increase, there emerges a unique potential for content design to provide a competitive edge among local competitors.

In short, the future of content design in China is marked by both ongoing challenges and promising directions, and as Sabrina Valles states:

“I believe influence and persuasion will continue to be crucial. Many clients still lack the understanding of why certain strategies work. Success stories may encourage increased spending, but education about content strategy is necessary.”

The journey of content design in China continues to unfold amidst challenges and new perspectives. Ongoing efforts signify a growing acknowledgment of its pivotal role. As companies aim for a global footprint, content design has emerged not just as a necessity but as a key differentiator, shaping transcultural user experiences.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and interviewees and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of any entities they represent.

Get our weekly Dash newsletter packed with links, regular updates with resources, discounts, and more.