One of the ways I’ve been trying to make a positive difference during this lost COVID-19 season is to hold office hours for unemployed or emerging UX writers. I hear over and over again from writers in other industries—journalists, marketing copywriters, technical writers, etc.—that they’re pretty interested in UX writing but just don’t know how to break into the field.

I get that. UX is an alluring, inscrutable beast that comes with its own set of jargon, terminology, and process. To an outsider, it’s hard to parse at best, and at worst seems like it’s intentionally built to shift goalposts and to keep outsiders out.

One of these big unknowns is, of course, the UX writing portfolio. This is one of the most commonly asked-about topics I’ve seen in my office hours and in the many coffees I’ve had over the years with newcomers to the field.

Specifically, I get asked some variation of these questions:

Those are great questions. I tried to tackle some of them in a Twitter thread a couple of weeks ago, but admittedly, that’s a terrible way to get a big idea out. So let’s approach these questions here!

Great question! Maybe you shouldn’t. I don’t have all the answers, but I am a sometimes-hiring manager on a small but crack team of UX writers and content strategists at Adobe! We’re responsible for driving (and sometimes writing) the interface language throughout our biiiig varied portfolio of apps. I’m typically in charge of scouting, recruiting, and hiring my team members myself, so I’ve developed some opinions and practices over the last few years.

I had a great conversation with some friends about this very topic recently, and the conclusion I’ve come to is that they shouldn’t be, but they are.

Why shouldn’t they be?

But why is a UX writing portfolio necessary, then?

I think this is a great opportunity to play with the various media out there. To me, it doesn’t matter if it’s a link to a “My Work” section of your website, a PDF, a Google Slides deck, or what.

Basically, there are two things that I look for:

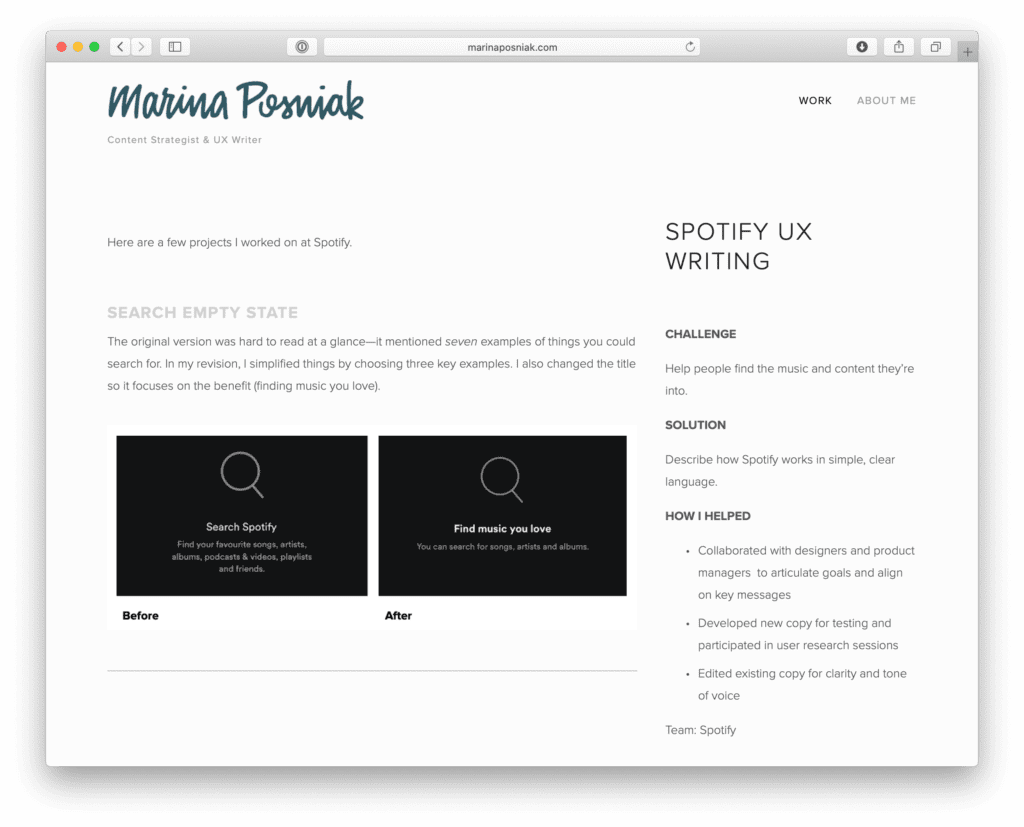

Let’s look at an example from what I think is an excellent portfolio. This is from Marina Posniak, a UX writer at Spotify. Of course, one big advantage she has is that Spotify is recognizable to most people—she doesn’t need to take the extra step of giving extra context. But she does a really great job of framing the specific, focused problem at hand:

She presents, on the right sidebar, an overview of the problem, the solutions she pursues, and how she contributed. On the left are a few, specific examples of that work in action. It’s very simple, and very focused, but she hits all the right information—this example shows how she reduced the text string from three lines to one, and why.

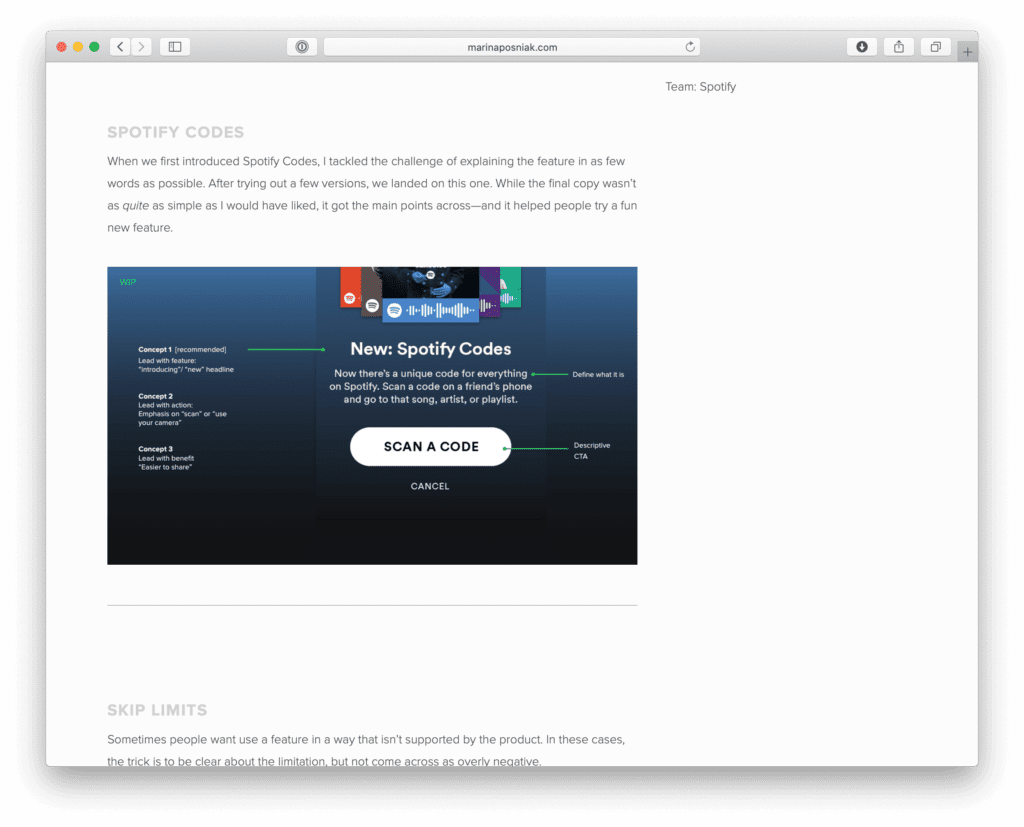

Here’s another great example—with the launch of Spotify Codes, Marina did something that’s very common for UX writers—she wrote a few different versions to see which one works best. And while she probably didn’t feel comfortable sharing the exact text of the versions that didn’t go live, she did a great job of summarizing what made the versions different.

If it includes these things, the rest is up to you! Andrea Drugay, Group Manager of Copy at Slack, made a good point when I was discussing this on Twitter.

She said, “A good UX writer is a good problem-solver, and a portfolio is, ultimately, a UX problem. How are you solving the problem of ‘How do I present my work?’ If you’re taking creative approaches to problem-solving, that’s a plus.”

That’s a great point. The way you put together your portfolio is a great meta-challenge, and a chance for you to shine at UX writing interviews.

This is pretty common. How can you be expected to show related examples if you don’t yet have experience?

There are certainly a few scrappy ways you can gain some UX experience without being a full-timer in the field:

But I think that you can get even scrappier. What kind of writing samples do you have? Magazine articles? Blog posts? Ad copywriting campaigns? We can work with that. It’s all about how you’re framing it.

Remember, writing is designing, and designing is about solving problems for the user. What was the problem, and how are you solving it with words?

You can probably answer those questions with your clips:

If the answer to these questions are, “I dunno, I just wrote some words”, then I can’t help you. UX writing (and these other writing industries, too) requires a baseline level of strategy and decision-making, and it’s very important to be able to give rationale. Your words should speak for themselves when they’re being reviewed, but you should always be able to show your approach and decision-making when you’re being reviewed.

Remember, there are no hard-and-fast rules to designing your UX writing portfolio. And I think you can use that ambiguity to your advantage. It’s a great design challenge in itself, and I really encourage you to experiment with the structure and form. As long as it’s accomplishing the right goals, and including the right information, you can exercise your communication and systems-thinking skills to really tell your story.

Andy Welfle is a Content Strategy Manager and hiring manager at Adobe Design in San Francisco, the centralized product design team at Adobe. Andy is also the co-author of “Writing is Designing: Words and the User Experience”. Follow him at @awelfle on Twitter or on the web at andy.wtf.

Get our weekly Dash newsletter packed with links, regular updates with resources, discounts, and more.